Some time ago, I had the requirement to use FreeBSD in a project, and soon the question came up if Docker and Kubernetes can be used.

On FreeBSD, Docker is not very well supported, and even if you can get it running, Linux is used in a Docker container. My experience with Docker on FreeBSD is awful, and so I started looking for alternatives.

- Note: The following blog explains how to install and set up Docker on FreeBSD -> How to setup docker in FreeBSD. The mentioned install procedure requires FreeBSD with a GUI — not suitable for GUI-less VMs hosted on Vultr or DigitalOcean.

A quick search on one of the most significant online search engines led me to Jails and then to BastilleBSD.

Bastille is an open-source system for automating deployment and management of containerized applications on FreeBSD. -- bastillebsd.org

BastilleBSD has an excellent Getting Started With Bastille guide, documentation, a lively blog, and a Youtube channel where all Bastille's features are explained in detail.

So in this blog post, I won't re-do the Bastille website, but instead, I'll go into the container technology history. I then look at the performance of Jails and FreeBSD. A comparison to Docker is not possible for me at this point.

TL;DR;

BastilleBSD is very promising. Practically negligible performance differences, active development, smart features (templates), and excellent documentation and guides are worth a recommendation.

Experimenting with Bastille is not only fun, but I also learn a lot about the internals of FreeBSD that I probably would not have looked at otherwise.

For those who want to use containers and depend on FreeBSD, Bastille is a severe alternative.

Check it out.

Content

- Access rights pitfalls and other dilemmas

- Pioneers of modern container technology

- BastilleBSD

- Experiences with BastilleBSD

- Appendix

Access rights pitfalls and other dilemmas

Under UNIX, the administration of user rights knows only two types of accounts: Users with and without administrator rights.

Nevertheless, this model quickly reaches its limits if, e.g., a web server has to be administrated. The web server administrator needs permission to change configurations or restart the webserver, but he must not change system settings or restart the machine. A solution could be to fine-tune the permissions, but this requires a much higher administration effort.

FreeBSD offers the ability to work with File Access Control Lists (FACL) or the Capability and Sandboxing Framework Capsicum. Unfortunately, this increases the administrative effort considerably, which in turn can harm security.

Pioneers of the modern container technology

Since 1979 chroot is part of version 7 Unix. Thus Unix is one of the oldest systems that can handle container management functions in the broadest sense.

chroot

chroot is an abbreviation that stands for 'change root' and allows you to change the root directory for the currently running process and all its child processes.

Image: Simple folder structure illustrating the view of the folders from a locked process (green)

A process that has been "rooted" in a directory and has no open file descriptors in the area outside the virtual root directory can no longer (if the operating system kernel is correctly implemented) access files outside this directory.

Chroot thus offered a simple way of locking untrustworthy or otherwise dangerous processes in a kind of sandbox. It is a simple "jail"-like mechanism, but one could easily escape from it.

chroot was not designed as a security feature but was primarily used for setting up virtual environments. The first major known application was in 1986 in Network Software Engineering (NSE) on SunOS, were leaving the environment with fchroot was possible and documented.

In practice, "chrooting" is made more difficult because programs expect to find space for temporary files, configuration files, device files, and program libraries at specific fixed locations when they are started. Running these programs within the chroot directory required the directory to be equipped with the necessary files.

Whether chroot environments are a security feature to seal off individual computer processes from the overall computer strongly depends on the view of the creators of the respective operating system:

Security feature or not?

Unix

BSD systems try not to let processes of the chroot environment break out, i.e., to lock them up. In this sense, the first appearance of the broad term "jail" is documented since 1991 with the Unix distribution 4.3BSD.

Historically, since 2000, BSD systems have offered operating system-level virtualization. The kernel is used by multiple isolated, completely closed units ("user space" instances, environments). This was preceded by the FreeBSD distribution, which provided the Unix command jail in version 4.0 (2000) to seal off process environments from each other securely. This led to the coining of the term "jailbreak" until 2004.

In Solaris before Solaris 10, chroot was not considered a security feature, so no problem was seen when a program could "escape" from this environment. The outbreak is even explicitly documented. The Solaris 10 release in 2005 introduced the concept of Solaris containers (also called zones). Zones were based on chroot and called "chroot on steroids". However, in Solaris 10 and later versions, many more properties were added, and file systems (such as the proc file system) were also explicitly protected against chroot.

Linux

- Also, under Linux, chroot is not called a security function. How the user root can leave a chroot environment is documented in the chroot man page.

- Starting in 2008, the LinuX Container LXC will enable creating virtual "user space" environments with their processes using a shared Linux kernel. The GNU/Linux Software Docker (2013) is was based on LXC, isolating applications in containers using operating system virtualization.

A more detailed view on the history is available here -> A Brief History of Containers: From the 1970s Till 2016.

Disadvantages

Only the root user can run chroot. This is to prevent normal users from putting a setuid program in a specially designed chroot environment (e.g., with a wrong /etc/passwd file), which would result in it granting privileges. However, it also prevents non-root users from using the chroot mechanism to create their sandbox.

The chroot mechanism itself is not entirely safe. Suppose a program has root privileges in a chroot environment. In that case, it can (under Linux or Solaris) use a nested chroot environment to break out of the first one.

Since most Unix systems are not fully filesystem oriented, potentially dangerous functionalities such as network and process control through system calls remain available to a chroot-enabled program.

Even the chroot mechanism itself does not impose any restrictions on resources such as I/O bandwidth, disk space, or CPU time.

jail

The jail mechanism is an implementation of FreeBSD virtualization at the operating system level, which allows system administrators to partition a FreeBSD-derived computer system into several independent mini-systems, called Jails, which all share the same kernel, with very little overhead.

Jails use the favorable properties of chroot while offering absolute protection against manipulating processes outside the prison. Since a "jail" is based on a subdirectory tree, a process inside the Jails can no longer access directories and files outside the "jail". Furthermore, it is no longer possible for a jailed process to manipulate the host's processes. This makes Jails the right choice for running network services in them.

However, Jails do not increase the safety of a demon itself. If an FTP daemon has a security hole, it has it in jail. An attacker could exploit this vulnerability to gain access to the Jails and possibly even gain root privileges – in jail.

Nevertheless, a significant security advantage would remain, since the attacker could only perform his mischief in the "jail". He would not have access to the host system! In contrast to fine-grained access management, the effort is only moderately increased. It is no longer possible to abort processes or influence other processes outside of a Jails.

In a Jails, there is again a root user, but with somewhat limited possibilities. Among other things, he has no opportunity to manipulate the host or the Jails' IP address.

Certain sysctl MIBs can limit the root's authority within a Jails.

It is possible to assign one or more IPv4 or IPv6 addresses to a Jails, making it a routable Jails. The address is specified when the Jails is started. The loopback address 127.0.0.1 and its IPv6 counterpart ::1 can be associated with a Jails. This is called an "internal jail".

Within Jails, the user has access to a complete FreeBSD. Thus Jails also offer a kind of virtualization like VMware or Xen.

Since FreeBSD 8, it is even possible to create additional Jails within a Jails (Hierarchical-Jails).

Restrictions

Within a Jails, there are essential restrictions due to the implementation. Remote Procedure Calls (RPC) no longer work in prison operation for security reasons. Therefore there is no possibility to use NFS within a Jails.

Daemon processes on the host must be configured very carefully to avoid address conflicts between a Jails and the FreeBSD host.

Loading or unloading kernel modules within a Jails are prevented and the creation of device nodes.

Mounting and de-mounting of file systems are not possible.

Changing network configuration, network addresses, or routing tables is prohibited.

Access to the host system's so-called raw sockets is no longer possible, but it is possible to access this kind of sockets within the' jail'.

It is also not allowed to address the semaphores of the host system.

Most of these limitations result in a security gain compared to a chrooted environment.

How is a process "locked" into a Jails?

In FreeBSD, each process is represented by a C structure proc described in /usr/include/sys/proc.h. It contains a pointer that points to the prison structure. The p_flag field with the value P_JAILED indicates that the process manager should be executed in a Jails.

The high level of protection is due to how the process management of the FreeBSD kernel processes the C structure struct proc.

As soon as a process is allocated computing time again by the time slice procedure, proc -> prison -> p_flag is used to check whether the process belongs to a Jails or not.

For processes started within a jail, this flag is set unconditionally. Many other kernel services use this flag to decide on each access, whether and how resources may be accessed.

Image: Simplified communication paths between Jails command and Jails systems call.

Using Jails

My experience with Jails is not yet strong enough to give correct instructions. Fortunately, the FreeBSD Foundation presented Jails extensively in one of its last Friday live streams.

If you don't want to watch the almost one-hour video presentation, you can also read a 16 step short guide Jails on FreeBSD" on how to jail first processes and applications.

BastilleBSD

Jails require in-depth knowledge of FreeBSD kernel calls, userland commands, and network and resource management (ZFS). Not every FreeBSD user has this knowledge, yet anyone should be able to "lock-up" untrusted processes and applications separately from the rest of the system. For this reason, projects like ezjail and Bastille, among others, have been developed.

What's unique about Bastille?

... aside from FreeBSD native Kernel features? Templates!

Templates help automate container setup. You can enhance a new set-up container, for example, Phoenix / Elixir, with the Node.js template. Phoenix relies on node and npm, which you can install manually or apply the already existing node template.

In Dockerland, you must trust the author who uploaded an image to the Docker registry, not so with Bastille as there is no image registry. Templares are shared in plain text. You always see what functionality you are going to apply to your container.

Performance

Docker has changed dramatically throughout time, but running Docker does not produce the same performance results on different operating systems as on each OS, Docker uses other OS native features.

Jails is a BSD *nix exclusive feature that avoids implementing abstraction layers that could impact performance when executing containerized applications.

However, what is the performance of applications running inside a Jails?

The execution of benchmarks is always tricky because other components can unintentionally influence measurements, which one potentially overlooks at first sight.

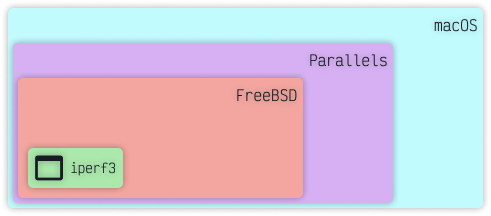

I choose iperf3 for testing network throughput performance as it's a single binary, and the same version is available on macOS and FreeBSD.

I ran all tests on my MacBook Pro 13" (2020).

Base config

I installed FreeBSD via Parallels and configured the FreeBSD instance after the cheapest VMs offered by Vultr and DigitalOcean.

Local Parallels Vultr DigitalOcean 1-CPU core 1-CPU core 1-CPU core 1024MB RAM 1024MB RAM 1024MB RAM 25GB SSD on NVMe + TRIM 25GB SSD 25GB SSD IPv4 IPv4 IPv4 12.1-RELEASE-p10 12.1-RELEASE-p10 12.1-RELEASE-p10 Boot flags:</ br>vm.bios.efi = 1 Instance:</ br>FreeBSD 12.1 x64 Droplet:</ br>FreeBSD 12.1 zfs x64 Table: Comparing the base configurations

Testing network performance of virtualized FreeBSD

macOS

$ iperf3 -v

$ iperf 3.9 (cJSON 1.7.13)

Darwin Dennys-MBP.fritz.box 19.6.0 Darwin Kernel Version 19.6.0: Mon Aug 31 22:12:52 PDT 2020; root:xnu-6153.141.2~1/RELEASE_X86_64 x86_64

Optional features available: sendfile / zerocopy, authentication

FreeBSD

$ iperf3 --version

iperf 3.9 (cJSON 1.7.13)

FreeBSD vFreeBSD 12.1-RELEASE-p10 FreeBSD 12.1-RELEASE-p10 GENERIC amd64

Optional features available: CPU affinity setting, SCTP, TCP congestion algorithm setting, sendfile / zerocopy, socket pacing, authentication

I used the following pf.conf for the virtualized FreeBSD.

ext_if="vtnet0"

set skip on lo

table <jails> persist

nat on $ext_if from <jails> to any -> ($ext_if)

Note: The pf.conf configuration above is NOT meant to be used in production as none of pf's security features are enabled. In fact, I removed every security aspect of the configuration to go as smoothly as possible for my tests.

Test 1 - running iperf server mode in virtualized FreeBSD

*Image: macOS running Parallels, running FreeBSD, executing iperf

FreeBSD: iperf3 -s

macOS: iperf3 -c 10.211.55.3 -P1

Connecting to host 10.211.55.3, port 5201

[ 5] local 10.211.55.2 port 61942 connected to 10.211.55.3 port 5201

[ ID] Interval Transfer Bitrate [ 5] 0.00-1.00 sec 453 MBytes 3.80 Gbits/sec [ 5] 1.00-2.00 sec 428 MBytes 3.59 Gbits/sec [ 5] 2.00-3.00 sec 392 MBytes 3.29 Gbits/sec [ 5] 3.00-4.00 sec 409 MBytes 3.43 Gbits/sec [ 5] 4.00-5.00 sec 451 MBytes 3.78 Gbits/sec

[ ID] Interval Transfer Bitrate [ 5] 0.00-5.00 sec 2.08 GBytes 3.58 Gbits/sec sender [ 5] 0.00-5.00 sec 2.08 GBytes 3.58 Gbits/sec receiver Table: Transfer details

Note: 1-CPU core is a very limiting factor. Transfer and Bitrate drops after 5 seconds or using -P2 and more simultaneous connections.

Test 2 - running `iperf server mode in macOS

macOS: iperf3 -s

FreeBSD: iperf3 -c 10.211.55.2 -P1 -t5

Connecting to host 10.211.55.2, port 5201

[ 5] local 10.211.55.3 port 46131 connected to 10.211.55.2 port 5201

[ ID] Interval Transfer Bitrate [ 5] 0.00-1.00 sec 1020 MBytes 8.55 Gbits/sec [ 5] 1.00-2.00 sec 1020 MBytes 8.55 Gbits/sec [ 5] 2.00-3.00 sec 979 MBytes 8.22 Gbits/sec [ 5] 3.00-4.00 sec 1023 MBytes 8.58 Gbits/sec [ 5] 4.00-5.00 sec 1014 MBytes 8.51 Gbits/sec

[ ID] Interval Transfer Bitrate [ 5] 0.00-5.00 sec 4.94 GBytes 8.48 Gbits/sec sender [ 5] 0.00-5.00 sec 4.94 GBytes 8.30 Gbits/sec receiver Table: Transfer details

Note: As macOS runs natively on my Macbook Transfer and Bitrate is not impacted and easily outperforms virtualized FreeBSD.

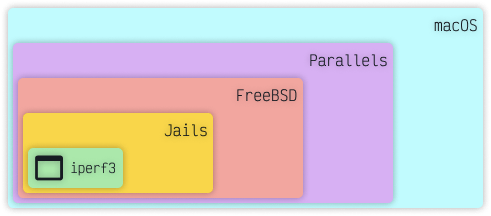

Test 3 - running iperf server mode in a jailed instance in virtualized FreeBSD

I changed my pf.conf configuration and added row 7 and row 8.

ext_if="vtnet0"

set skip on lo

table <jails> persist

nat on $ext_if from <jails> to any -> ($ext_if)

# forward iperf3 traffic incoming on port 5201 to Jails with local IPv4 10.0.0.1

rdr pass inet proto TCP from any to any port {5201} -> 10.0.0.1

*Image: macOS running Parallels, running FreeBSD, running Jails, executing iperf.

To run iperf3 in server mode inside the jailed FreeBSD instance, I needed to bind the server to the Jails container's local network interface.

jailed-FreeBSD: iperf3 -B 10.0.0.1 -s

macOS: iperf3 -c 10.211.55.3 -P1 -t5

Connecting to host 10.211.55.3, port 5201

[ 5] local 10.211.55.2 port 61708 connected to 10.211.55.3 port 5201

[ ID] Interval Transfer Bitrate [ 5] 0.00-1.00 sec 473 MBytes 3.97 Gbits/sec [ 5] 1.00-2.00 sec 423 MBytes 3.54 Gbits/sec [ 5] 2.00-3.00 sec 410 MBytes 3.44 Gbits/sec [ 5] 3.00-4.00 sec 485 MBytes 4.07 Gbits/sec [ 5] 4.00-5.00 sec 243 MBytes 2.03 Gbits/sec

[ ID] Interval Transfer Bitrate [ 5] 0.00-5.00 sec 1.99 GBytes 3.41 Gbits/sec sender [ 5] 0.00-5.00 sec 1.99 GBytes 3.41 Gbits/sec receiver Table: Only 170MBits/s difference between the virtualized FreeBSD (3.58 GBits/sec) and the jailed instance on the virtualized FreeBSD (3.41 GBits/sec).

Performance conclusion

I ran the tests several times and saw different test results until I got the 'pf.conf' configuration right. To my surprise, the pure network performance is not significantly affected. I would even say it is only slightly affected and can be ignored in many cases.

Nevertheless, an essential cornerstone for the performance is the packet filter firewall configuration. My knowledge of PF is not yet sufficient to keep security aspects switched on and still achieve high performance.

In my local environment, I have run FreeBSD with 4 CPU cores, and the performance reached almost the macOS level. However, as soon as I changed from server-mode to client-mode or vice versa, the performance caved. I guess configuration errors are pervasive because Jails depend on NAT, and the more complex the firewall rules, the more vulnerable the performance - especially on machines with only 1 or 2 CPU cores.

I repeated the tests in my DigitalOcean environment, but I could not get stable results because my $5 instances do not seem to be a priority and network performance, therefore, fluctuated a lot - too much to be shown here until I find someone to pay for a much bigger Droplet cluster. 😉

Experiences with BastilleBSD

Bastille only issues Jails and (if configured) ZFS commands.

To use the Bastille well, you need to know Jails and ZFS.

I am not a professional user of either Jails or ZFS.

For a side project, I needed Erlang in major version 23.x, but pre-compiled packages are only available for major version 21.x.

At the moment, Bastille can only install packages with the pkg' subcommand. To install much more recent packages for FreeBSD, you can use theports' source tree.

Until Bastille supports ports, you have to help yourself using the Bastille cp subcommand.

My workflow currently looks like this. I install the latest package on the jails container with bastille pkg <target-container> <package-name>. Then I compile the newer version directly on FreeBSD from the ports sources. Then I search the target jails container with Bastille subcommand console to note the paths where pkg has installed the packages. Finally, I use the Bastille subcommand cp and copy all the files in the middle of the ports create files to the place where pkg installed the outdated package.

This is tedious, time-consuming, and error-prone.

A little trick I just learned is to make ZFS snapshots before and after the installation and then compare the ZFS snapshots (zfs diff).

Jailing applications with Bastille usually works on the first go.

The network configuration is still a little bit difficult. pf.conf and resolv.conf are the two files I have to change frequently to "try out" how to reach an application from outside or how jailed processes can reach each other.

Sometimes I configured the wrong ports or was not aware that UDP is used instead of TCP. Sometimes a process needs to be configured to 'bind' to the virtual network interface instead of the local private IP.

After a couple of weeks now, I usually only need less than an hour to get new containers up and running.

It is noticeable for side projects when I only have to pay $5 for virtual machines on Vultr or DigitalOcean instead of $10 or $20.

I do not like Kubernetes and Docker that much, and now I am thrilled to have found an alternative that works well and does not drill deep into my wallet.

State of Bastille

Bastille is reasonably young and still under development. Development happens on GitHub while templates are hosted on GitLab. You can find out about essential additions or changes on the blog here -> Bastille Blog or follow BastilleBSD on Twitter.

Appendix

Other Jails management tools worth noting:

(Alphabetical order)

Useless stats:

406 Lines

3481 Words

25334 Characters